“The Left is rather prone to a perspective according to which the class struggle is something waged by the workers and the subordinate classes against the dominant ones.

It is of course that. But class struggle also means, and often means first of all, the struggle waged by the dominant class, and the state acting on its behalf, against the workers and the subordinate classes. By definition, struggle is not a one way process; but it is just as well to emphasize that it is actively waged by the dominant class or classes, and in many ways much more effectively waged by them than the struggle waged by the subordinate classes.”

Ralph Miliband, “The Coup in Chile” (1973)

The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon ranks as perhaps Karl Marx’s greatest historical work. In the essay, he documents the events that culminated in the 1851 seizure of power in France by Louis Napoleon, nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte. His study of the French commercial bourgeoisie, the urban working class, and the “grotesque mediocrity” that was Louis Napoleon himself are descriptive only of a certain time and place, but the analysis of class struggle provides a useful inspiration Marxist scholars interpreting critical junctures past and present. For example, the rise of fascism in the West during the early 20th century played out in a manner comparative to the spread of liberal values in the late 19th century, just as the latter had a profound effect on the parameters set on the former. As the West enters another period of unrest, a similar class struggle is occurring. With neoliberalism under threat, elites are uniting with right-wing populists to frustrate and prevent popular challenges from the left.

The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon ranks as perhaps Karl Marx’s greatest historical work. In the essay, he documents the events that culminated in the 1851 seizure of power in France by Louis Napoleon, nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte. His study of the French commercial bourgeoisie, the urban working class, and the “grotesque mediocrity” that was Louis Napoleon himself are descriptive only of a certain time and place, but the analysis of class struggle provides a useful inspiration Marxist scholars interpreting critical junctures past and present. For example, the rise of fascism in the West during the early 20th century played out in a manner comparative to the spread of liberal values in the late 19th century, just as the latter had a profound effect on the parameters set on the former. As the West enters another period of unrest, a similar class struggle is occurring. With neoliberalism under threat, elites are uniting with right-wing populists to frustrate and prevent popular challenges from the left.

The Past is Prologue

In 1848 liberal revolutions swept through western Europe, a sign that “rule by the sword and monk’s cowl” would no longer be accepted in the embrace of logic and reason post-Enlightenment. The turn to commercial agriculture had produced the bourgeoisie, who demanded greater freedoms and political participation. In France, the revolution started out peaceful a “matter of course,” with the “bourgeois monarchy” replaced with a “bourgeois republic” promoted by “the aristocracy of finance, the industrial bourgeoisie, the middle class, the petty bourgeois, the army, the lumpen proletariat…, the intellectual lights, the clergy, and the rural population.” Marx notes that this ruling class used force to put down a proletarian uprising in late June, in which thousands were killed, ending the “universal-brotherhood swindle.” Much more attention is passed to the following years, as Louis Napoleon is first elected president in December 1848, his struggle for power with various bourgeois factions, ending with the 1851 coup and the Napoleonic victory over the bourgeoisie. Replace Louis Napoleon with Hitler or Mussolini and we see parallels with moderate liberals underestimating megalomaniacal tyrants. In the modern age, we are still in the early days, but the prospect of democratic breakdown seems increasingly possible given dismal trust in major institutions, especially in political parties and governmental bodies. As before, there seems to be one element in common: liberal elites forming pacts with anti-democratic reactionaries in alliance against the working class, even at the (remarkably high) risk of right-wing betrayal.

In 1848 liberal revolutions swept through western Europe, a sign that “rule by the sword and monk’s cowl” would no longer be accepted in the embrace of logic and reason post-Enlightenment. The turn to commercial agriculture had produced the bourgeoisie, who demanded greater freedoms and political participation. In France, the revolution started out peaceful a “matter of course,” with the “bourgeois monarchy” replaced with a “bourgeois republic” promoted by “the aristocracy of finance, the industrial bourgeoisie, the middle class, the petty bourgeois, the army, the lumpen proletariat…, the intellectual lights, the clergy, and the rural population.” Marx notes that this ruling class used force to put down a proletarian uprising in late June, in which thousands were killed, ending the “universal-brotherhood swindle.” Much more attention is passed to the following years, as Louis Napoleon is first elected president in December 1848, his struggle for power with various bourgeois factions, ending with the 1851 coup and the Napoleonic victory over the bourgeoisie. Replace Louis Napoleon with Hitler or Mussolini and we see parallels with moderate liberals underestimating megalomaniacal tyrants. In the modern age, we are still in the early days, but the prospect of democratic breakdown seems increasingly possible given dismal trust in major institutions, especially in political parties and governmental bodies. As before, there seems to be one element in common: liberal elites forming pacts with anti-democratic reactionaries in alliance against the working class, even at the (remarkably high) risk of right-wing betrayal.

In a series of articles detailing the class antagonisms of the 1848 revolution in France, Marx writes that it “was not the French bourgeoisie that ruled under Louis Philippe, but one faction of it: bankers, stock-exchange kings, railway kings, owners of coal and iron mines and forests, a part of the landed proprietors associated with them—the so-called financial aristocracy.” The downfall of the monarchy had as its chief objective “to complete the rule of the bourgeoisie by allowing, besides the finance aristocracy, all the propertied classes to enter the orbit of political power.” The bank is the “high church” to the financial aristocracy, and rather than letting the state fall into bankruptcy, the provisional bourgeois government seeks a “patriotic sacrifice” in a new tax on the peasantry. What is more, the bourgeois republic swiftly turned against the working class, with one minister remarking: “The question now is merely one of bringing labor back to its old conditions.” The proletarians of Paris revolted in the “June days,” which prompted a massacre of thousands. Across Europe, a similar pattern repeated as the continental bourgeoisie “league[d] itself openly with the feudal monarchy against the people,” with the bourgeoisie becoming victims themselves in the aftermath of the revolutionary era. Reactionary counterrevolutions were widespread and repressive, particularly in Russia. To the extent that western European states implemented liberal reforms in subsequent decades, it was not in response to revolution, but gradual reforms undertaken by bourgeois political parties in concert with the financial aristocracy and other elites from the old political order. These groups shared a common fear of the working class and organized labor, whom they proceeded to keep out of power.

Over time, the continued agitation of organized labor movements (including political parties affiliated with trade unions) as well as greater public awareness of extreme poverty, mass illiteracy, and high mortality among the working poor turned the “classical liberalism” of Adam Smith to the “social liberalism” of Leonard Hobhouse. Western European governments began introducing reform packages including old age pensions, free school meals, and national health insurance. In Germany, the conservative statesman Otto von Bismarck created the first modern welfare state in a successful bid to stave off competition from socialist rivals. These strategic concessions by elites inspired some on the political left to argue socialism could be implemented in a similar vein, through incremental legislative reforms. In the U.K., this school of thought was embodied by the Fabian Society, whose members included two co-founders of the London School of Economics, Sidney and Beatrice Webb, as well as the Irish playwright and activist George Bernard Shaw. In Germany, social democratic politician Eduard Bernstein served as principal theorist in articulating a modified version of Marxism, where socialism would not come through violent revolution but by peaceful, lawful means. Bernstein even cited the repression of the Parisian proletariat in 1848 as an example of why revolution was actually a path to reactionary victory, not socialism.

In response to Bernstein’s revisionism, the German communist Rosa Luxemburg wrote a pamphlet in 1899, Social Reform or Revolution?, arguing that accumulative state-sanctioned reform “is not a threat to capitalist exploitation, but simply the regulation of exploitation. …[I]n the best of labor protective laws, there is no more ‘socialism’ than in a municipal ordinance regulating the cleaning of streets or the lighting of streetlamps.” According to her, the political participation of the working class in democratic societies is ultimately fruitless because “class antagonisms and class domination are not done away with, but are, on the contrary, displayed in the open.” In other words, the parties vying for power in legislatures take on the class character of the constituencies: a Conservative Party for the traditional ruling class, a Liberal Party for the commercial bourgeoisie, a Labour Party for the working class, and so on. Yet capitalism is fundamentally about the economy and economic power, not politics or laws. For Luxemburg, just as it was for Marx, the route to proletarian liberation was not through parliaments, but through a dictatorship of the proletariat, with the absolute class dominance of the working class over others. Only through this complete reversal in class relations could the workers of the world seize the means of production and build real, lasting socialism. Even as Luxemburg later became a critic of the Bolsheviks for what she claimed were undemocratic practices, she never endorsed liberal democracy as a credible avenue for rescuing the working class from their oppressed, exploited state.

The Ruling Class and Fascism

In 1919, right-wing paramilitaries operating under orders from the social democratic German government murdered Luxemburg and tossed her body in a Berlin canal. That social democratic politicians, ostensibly dedicated to building socialism, would use such methods against the revolutionary communist opposition seemed to validate the criticisms by the communists that reform-minded social democrats would, in the end, align themselves with the ruling class instead of ordinary workers. This was borne out by other examples. In early 1929, the Berlin police, directed by the social democratic government, used vicious force to put down banned communist rallies on May Day. Dozens died, most of them innocent bystanders and not communists at all. In the U.K., the 1929 Great Depression led to first ever Labour Party election victory, but rather than pursue socialist policies, Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald formed a “National Government” with the Conservative and Liberal parties, betraying his left-wing blue-collar base. In France and the U.S., social liberals were able to placate anger and anxiety over the economic crisis by finally creating welfare states, including the New Deal policies of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, while maintaining capitalist economies.

In Germany and Italy, however, resentments instilled by World War I and the effects of the Wall Street stock market crash left conservative and liberal politicians exposed to populist grievances. This led to a surge in popularity for the far left and the far right in both countries. Notably, neither Adolf Hitler in Germany nor Benito Mussolini in Italy came into government by force; rather, they were appointed by elder statesmen, Hitler by President Paul von Hindenburg, and Mussolini by King Victor Emmanuel III. Although both men later seized absolute power, they had the support of the upper and middle classes, especially the petty bourgeoisie. Democracy was destroyed, but in both cases, capitalism was maintained. Hitler collaborated with German industrialists, with private companies designing everything from Nazi uniforms (Hugo Boss) to aircraft engines (Daimler-Benz, owner of Mercedes-Benz). The Italian automobile manufacturer Fiat produced machinery for Mussolini’s armed forces as well. Just as today, war was good business, and companies were keen to profit from it. Meanwhile, trade unions were abolished, and labor issues became a matter for the state to regulate. Contemporary right-wingers in the West often attempt to portray Nazi Germany or fascist Italy as “socialist” or “communist” in ideology or character, but truthfully they shared an intense hatred for Marxism and the Soviet Union (along with Japan, the two future Axis powers were signatories to the 1936 Anti-Comintern Pact, an informal alliance explicitly aimed at opposing Moscow and the spread of communism.

In Germany and Italy, however, resentments instilled by World War I and the effects of the Wall Street stock market crash left conservative and liberal politicians exposed to populist grievances. This led to a surge in popularity for the far left and the far right in both countries. Notably, neither Adolf Hitler in Germany nor Benito Mussolini in Italy came into government by force; rather, they were appointed by elder statesmen, Hitler by President Paul von Hindenburg, and Mussolini by King Victor Emmanuel III. Although both men later seized absolute power, they had the support of the upper and middle classes, especially the petty bourgeoisie. Democracy was destroyed, but in both cases, capitalism was maintained. Hitler collaborated with German industrialists, with private companies designing everything from Nazi uniforms (Hugo Boss) to aircraft engines (Daimler-Benz, owner of Mercedes-Benz). The Italian automobile manufacturer Fiat produced machinery for Mussolini’s armed forces as well. Just as today, war was good business, and companies were keen to profit from it. Meanwhile, trade unions were abolished, and labor issues became a matter for the state to regulate. Contemporary right-wingers in the West often attempt to portray Nazi Germany or fascist Italy as “socialist” or “communist” in ideology or character, but truthfully they shared an intense hatred for Marxism and the Soviet Union (along with Japan, the two future Axis powers were signatories to the 1936 Anti-Comintern Pact, an informal alliance explicitly aimed at opposing Moscow and the spread of communism.

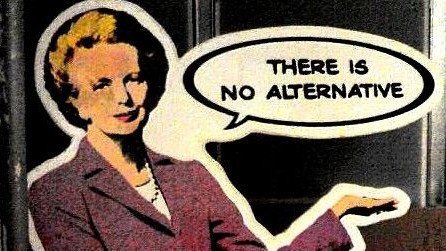

Domestically, Nazi Germany and fascist Italy rounded up political prisoners and placed them in jails or concentration camps, many of them from radical left-wing parties. In Italy, this included one of the founders of the Italian Communist Party, Antonio Gramsci. An activist who organized industrial action at Fiat factories, Gramsci was also a Marxist theorist, his primary contribution being the idea of “cultural hegemony.” According to Gramsci, the ruling class no longer needs to rely on force or the threat of force to exercise social control. Instead, the subordinate classes adopt the norms, ideas, and values of the dominant group, internalizing them as their own. Civil society in capitalist societies create and consolidate this cultural hegemony through institutions separate from the state (schools, places of worship, even family units) that nevertheless encourage and reinforce acceptance of the status quo. The role of religion in bolstering those in power while also functioning as an “opiate of the masses” is well-known, but practices like reciting the “Pledge of Allegiance” in a classroom or deferring to “father knows best” in family matters also develop submission to authority. Presenting the default quality of human nature to be self-interested and egocentric contributes to the perception of capitalism as normal, innate to humanity itself. In this way perspectives critical to maintaining and expanding capitalism and the power of the ruling class become “common sense” and “conventional wisdom.” It becomes easier in the popular imagination to imagine the world endling than it does to imagine a world without the dominant economic and political systems. This is reflected in a slogan employed by Margaret Thatcher in her promotion of neoliberal economics: “There is no alternative.”

The Case of Spain: Sociological Francoism

In July 1936, civil war erupted in Spain between the popularly elected left-wing government and right-wing rebels, the latter eventually headed by General Francisco Franco. After the victory of the rebels in 1939, Franco became the dictator of Spain and would remain so until his death in 1975. While not explicitly fascist, the Franco regime was undeniably authoritarian-conservative, favoring militaristic nationalism and very traditional Roman Catholicism. Political opponents in Francoist Spain were brutally repressed by state law enforcement agencies, with death warrants personally signed by Franco himself. The government, however, also implemented was is now termed “sociological Francoism,” the internalization in the Spanish public of ideas and values that supported the dictatorship. The government only recognized Castilian Spanish as the “official language” of Spain, denying the reality that tens of thousands of Spanish citizens spoke other languages, such as the Catalan and Basque languages. The Catholic Church had authority over Spanish schools and teachers who were judged to be insufficiently pious were dismissed from their posts. The orphans of parents who had fought for or supported the left-wing government during the civil war were turned over to Catholic orphanages and taught that their parents had been terrible sinners. State propaganda substantiated patriarchal gender roles, with men encouraged to be proud, aggressive warriors and women to be obedient, unassuming mothers and housekeepers.

In July 1936, civil war erupted in Spain between the popularly elected left-wing government and right-wing rebels, the latter eventually headed by General Francisco Franco. After the victory of the rebels in 1939, Franco became the dictator of Spain and would remain so until his death in 1975. While not explicitly fascist, the Franco regime was undeniably authoritarian-conservative, favoring militaristic nationalism and very traditional Roman Catholicism. Political opponents in Francoist Spain were brutally repressed by state law enforcement agencies, with death warrants personally signed by Franco himself. The government, however, also implemented was is now termed “sociological Francoism,” the internalization in the Spanish public of ideas and values that supported the dictatorship. The government only recognized Castilian Spanish as the “official language” of Spain, denying the reality that tens of thousands of Spanish citizens spoke other languages, such as the Catalan and Basque languages. The Catholic Church had authority over Spanish schools and teachers who were judged to be insufficiently pious were dismissed from their posts. The orphans of parents who had fought for or supported the left-wing government during the civil war were turned over to Catholic orphanages and taught that their parents had been terrible sinners. State propaganda substantiated patriarchal gender roles, with men encouraged to be proud, aggressive warriors and women to be obedient, unassuming mothers and housekeepers.

While politically illiberal, Francoist Spain embraced economic liberalism, attracting around $8 billion in foreign direct investment and a booming tourism business. Despite the obviously tyrannical nature of the government, corporations and bourgeois holiday-goers were keen to profit from opportunities available in the country. It was easier to ignore and welcome the harshness directed at left-wing dissidents than to take a principled stand, especially for those sectors of Spanish society that had no natural sympathy for the cultural minorities or the militant working class. Francoist Spain helped to demonstrate that economic prosperity and a relatively high standard of living can eclipse notions of political liberty and civil responsibility for a majority of social groups, contrary to what liberal idealists would claim. The growth of the Spanish economy for fifteen years, from $12 billion to $76 billion, kept Francoism secure.

When Franco died in 1975, a democratization process occurred in which political parties from the left and right forged an agreement called the “Pact of Forgetting.” There would be no formal reckoning with the human rights abuses and repression of dissent that had occurred during Francoist rule. Individuals and institutions who had blood on their hands were allowed to continue in public life. The Spanish 1977 Amnesty Law (still in force today) granted immunity to perpetrators of atrocities from any prosecution or punishment. This consensus to avoid dealing with the crimes of the past meant that Spanish society did not polarize in the aftermath of Francoism, ensuring a stable and sustainable transition to a peaceful democracy rather than chaos and division leading to another potential civil war. Justice was sacrificed for political order and national unity.

In 2007, a center-left government in Spain passed a law intended to overturn the “Pact of Forgetting” and to finally recognize the rights of victims who suffered during the civil war and the dictatorship by rehabilitating the reputation of political prisoners, identifying those killed in summary executions and buried in unmarked graves, and removing Francoist symbols from public life. In 2014 a report made by the United Nations Commissioner for Human Rights found that implementation of the law was “timid” and that only three regions had supplied any meaningful effort in trying to locate people who had gone missing during the Franco years. Today, the major center-right political party in Spain, the People’s Party, traces its origins to Manuel Fraga, a former Francoist minister who oversaw the gradual, highly compromised transition from dictatorship to democracy. The People’s Party strongly opposed the passage of the 2007 law to finally deal with the repression of the Franco era, claiming it was “an argument for political propaganda.” Many works of art censored under Franco are still published in their censored or expurgated forms. Most recently, the People’s Party has been losing ground politically to a far-right party, Vox, which in addition to being openly xenophobic and sexist also expresses unreserved nostalgia for the Franco regime. While Franco’s formal dictatorship no longer exists, the cultural hegemony it utilized is still in place, with generations of Spaniards past and present conditioned to view the dark years of Francoism as not only far and respectable but even desirable. Today some Spaniards still openly lament: “Con Franco vivíamos major” (“We lived better with Franco”).

The Cultural Hegemony of Today

Just as the unrest of 1848 and the 1920s were ultimately triumphs for reactionaries, it seems that the present global tension is boosting the extreme right. The rise of Vox in Spain has its parallels in the U.S. “alt-right,” the arch-Brexiteers in the U.K., far-right populists in Brazil, ad nauseum. A large reason for this trend is that, culturally, these movements have received greater tolerance and even acceptance in these countries than left-wing movements typically spearheaded and supported by the younger generation. In societies where repressive violence is widely considered incongruent with liberal values, left-wing challenges are instead frustrated through unfavorable media coverage and social bias against unconventional progressive proposals. For example, universal health care is generally regarded with disbelief and skepticism as a dangerous, extreme policy despite the fact that almost all industrialized countries have some form of it. Calls to abolish NATO, explicitly set up to combat the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact countries, are dismissed as absurd despite the fall of the Soviet Union and its Eastern Europe allies several decades ago. Meanwhile, appeals to the principles of the past, despite being steeped in prejudice and ignorance by modern standards, at least have the virtue of familiarity. In other words, in the minds of many people, it is safer to go back than forward, even if it is at the expense of marginalized, vulnerable communities who have only just received some modicum of social justice after decades of fierce struggle.

Just as the unrest of 1848 and the 1920s were ultimately triumphs for reactionaries, it seems that the present global tension is boosting the extreme right. The rise of Vox in Spain has its parallels in the U.S. “alt-right,” the arch-Brexiteers in the U.K., far-right populists in Brazil, ad nauseum. A large reason for this trend is that, culturally, these movements have received greater tolerance and even acceptance in these countries than left-wing movements typically spearheaded and supported by the younger generation. In societies where repressive violence is widely considered incongruent with liberal values, left-wing challenges are instead frustrated through unfavorable media coverage and social bias against unconventional progressive proposals. For example, universal health care is generally regarded with disbelief and skepticism as a dangerous, extreme policy despite the fact that almost all industrialized countries have some form of it. Calls to abolish NATO, explicitly set up to combat the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact countries, are dismissed as absurd despite the fall of the Soviet Union and its Eastern Europe allies several decades ago. Meanwhile, appeals to the principles of the past, despite being steeped in prejudice and ignorance by modern standards, at least have the virtue of familiarity. In other words, in the minds of many people, it is safer to go back than forward, even if it is at the expense of marginalized, vulnerable communities who have only just received some modicum of social justice after decades of fierce struggle.

It is doubtful that the present social control protecting the ruling class and favoring reactionaries will falter until there is the development of what Gramsci described as “counterhegemonic culture.” For Gramsci, cultural hegemony is not monolithic; it is borne from social and class struggle that it, in turn, molds and influences. Cultural hegemony is therefore a contested and shifting set of ideas. In the U.S., it is notable that the predominant counterhegemonic critique is less radical than it is sometimes treated in the mainstream press; the “socialism” equated with U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders, the embodiment of the left-wing attack on the status quo, is more evocative of the welfare state policies of the New Deal era or many modern European capitalist countries. Millennial Americans, while typically more empathetic and more tolerant than past generations, are also less militant than their historical counterparts when it comes to political action. Recent so-called flashpoints of left-wing opposition, such as the 2011 Occupy Wall Street movement and 2017 Women’s March, have had festival atmospheres rather than the rage-fueled confrontations with authorities that were characteristic of the 2011 Tahrir Square protests in Egypt or the 2019 Hong Kong demonstrations. Western counterculture is still defined by individuality and avant-garde attitudes, but now more than ever also takes place through professional commercial operations. Music festivals and events of “radical self-expression” like Burning Man are less threats to the status quo than sanctioned profit-making avenues for “sticking it to the man” without actually risking real consequences through acts of civil disobedience and resistance.

The answer for this absence of popular revolt and meaningful counterhegemonic culture may be our own sociological sickness, a nostalgia for the neoliberal golden age of the 1980s-1990s. Western liberal societies did not have the pseudo-fascist traits of Franco’s Spain, but there are parallels with a period of economic prosperity coupled with indirect state violence against social “undesirables” (the ignored AIDs epidemic and the vilification of black “welfare queens” in the U.S., the industrial decline and racial tensions of Thatcher’s Britain). Also, just as the Spanish Civil War and the right-wing victory destroyed a powerful left-wing movement in Spain, the failure of 1960s protest in the West to enact real reform led to the virtual demise of a significant organized left-wing mobilization for the rest of the 20th century. Spaniards who grew up in Franco’s Spain were conditioned to accept the regime and its values as “normal” and correct; so too did many Westerners grow up in an environment where counterculture was a fun outlet for the weekends rather than a long, drawn-out struggle. While Western left-wingers may chant “Another world is possible,” it must be asked whether they have either the imagination to picture such a world, or the discipline to ever realize it.

Recently, right-wing opinion columnist Daniella Greenbaum

Recently, right-wing opinion columnist Daniella Greenbaum  It did not remain live for long. Business Insider pulled the piece after the inevitable backlash. As has become vogue for conservative commentators, Greenbaum cried censorship and sent out her resignation letter. Also, a litany of her ilk attended her self-pity party, with the usual cast of characters – Bret Stephens, Christina Hoff Sommers, John Podhoretz, Bethany Mandel, Jamie Kirchik, et al – rallying to her cause. Of course, rather than being blacklisted by the “liberal media,” Greenbaum found a new home at the Washington Post, where her first piece– you guessed it – bemoaned the death of “free speech” and the inclination by people to give in to the tyranny of the “mob.”

It did not remain live for long. Business Insider pulled the piece after the inevitable backlash. As has become vogue for conservative commentators, Greenbaum cried censorship and sent out her resignation letter. Also, a litany of her ilk attended her self-pity party, with the usual cast of characters – Bret Stephens, Christina Hoff Sommers, John Podhoretz, Bethany Mandel, Jamie Kirchik, et al – rallying to her cause. Of course, rather than being blacklisted by the “liberal media,” Greenbaum found a new home at the Washington Post, where her first piece– you guessed it – bemoaned the death of “free speech” and the inclination by people to give in to the tyranny of the “mob.” Much has already been made about t

Much has already been made about t Uniformly white and privileged, the right-wing chattering class prone to complaining about “censorship” reflect the genteel face of middle- and upper-class of the Caucasian U.S. that is both uncomfortable with the populism of Trump and the progressivism of the political left. Like the Trumpists, though, they despise “political correctness” – that is, the shifting norms and ideas around everything from class to race to gender – and the abandonment of “common sense” – that is, the prejudices and beliefs socialized into their heads as objective truth. Going back to the French Revolution, conservative forebear Edmund Burke argued that the “natural order” of society, embodied in the countryside, was under assault by a destructive working-class movement. Of course, we know now there is no “natural order” of society, that liberalism and capitalism are no more our natural condition than feudalism or slavery was. In the conservative mind, however, the past is something sacred, the “correct” arrangement, even if – as is now widely recognized – such an arrangement depends on the exclusion and suffering of certain groups. Perhaps the most fundamental rejoinder to conservative diatribes like Burke’s is that his idyllic England was no paradise to anyone who was not a straight cisgender property-owning white man. When Burke sought to expose the looting of the Indian subcontinent in the 1780s, it was not to denounce the brutality of imperialism, but to criticize its effect of creating boorish parvenus who threatened to disrupt business as usual with their new wealth. Burke succeeded in turning British imperialism into a national project, enriching and ennobling Britain off the plunder and subjugation of conquered peoples. Implied in Burke’s conservatism is a white supremacy, an ethnic nationalism that views English culture as innately superior to all others. U.S. culture imported this feature from Britain and used it to inspire “Manifest Destiny” and then “American Exceptionalism,” the crafting of a North American empire and then a global one as the self-styled champion of democracy and individual liberty, also ruled by a privileged class of mostly straight cisgender Caucasian men. When right-wing pundits today deplore the “disappearance of common sense,” what they mean is they lament the eroding of age-old ideological constructs that legitimate a status quo predicated on the exploitation of others.

Uniformly white and privileged, the right-wing chattering class prone to complaining about “censorship” reflect the genteel face of middle- and upper-class of the Caucasian U.S. that is both uncomfortable with the populism of Trump and the progressivism of the political left. Like the Trumpists, though, they despise “political correctness” – that is, the shifting norms and ideas around everything from class to race to gender – and the abandonment of “common sense” – that is, the prejudices and beliefs socialized into their heads as objective truth. Going back to the French Revolution, conservative forebear Edmund Burke argued that the “natural order” of society, embodied in the countryside, was under assault by a destructive working-class movement. Of course, we know now there is no “natural order” of society, that liberalism and capitalism are no more our natural condition than feudalism or slavery was. In the conservative mind, however, the past is something sacred, the “correct” arrangement, even if – as is now widely recognized – such an arrangement depends on the exclusion and suffering of certain groups. Perhaps the most fundamental rejoinder to conservative diatribes like Burke’s is that his idyllic England was no paradise to anyone who was not a straight cisgender property-owning white man. When Burke sought to expose the looting of the Indian subcontinent in the 1780s, it was not to denounce the brutality of imperialism, but to criticize its effect of creating boorish parvenus who threatened to disrupt business as usual with their new wealth. Burke succeeded in turning British imperialism into a national project, enriching and ennobling Britain off the plunder and subjugation of conquered peoples. Implied in Burke’s conservatism is a white supremacy, an ethnic nationalism that views English culture as innately superior to all others. U.S. culture imported this feature from Britain and used it to inspire “Manifest Destiny” and then “American Exceptionalism,” the crafting of a North American empire and then a global one as the self-styled champion of democracy and individual liberty, also ruled by a privileged class of mostly straight cisgender Caucasian men. When right-wing pundits today deplore the “disappearance of common sense,” what they mean is they lament the eroding of age-old ideological constructs that legitimate a status quo predicated on the exploitation of others. Greenbaum, a Jew and a Zionist, may not be aware that by following in Burke’s footsteps she is walking a path historically littered with anti-Semitism. The mirror image of the conservative utopia (white, tied to the land, patriotic) is the rootless, unscrupulous, and stateless subversive – in other words, for much of Western culture, the anti-Semitic caricature of the Jew. For Burke, the cause of the French Revolution’s degeneration into bloodshed was an unholy alliance between the working-class “rabble” and the “Old Jewry.” It may be more apt to say Greenbaum follows in the tradition of the British Prime Minister Benjamin Disiraeli, a Jew, who argued Jews were inherently conservative because of their racial self-consciousness and “accumulated wealth.” During the 1848 revolutions, however, he decried “the once loyal Hebrew” among the ranks of “the Leveller,” seeking the destruction of Christianity and the abrogation of private property (see Domenico Losurdo’s excellent

Greenbaum, a Jew and a Zionist, may not be aware that by following in Burke’s footsteps she is walking a path historically littered with anti-Semitism. The mirror image of the conservative utopia (white, tied to the land, patriotic) is the rootless, unscrupulous, and stateless subversive – in other words, for much of Western culture, the anti-Semitic caricature of the Jew. For Burke, the cause of the French Revolution’s degeneration into bloodshed was an unholy alliance between the working-class “rabble” and the “Old Jewry.” It may be more apt to say Greenbaum follows in the tradition of the British Prime Minister Benjamin Disiraeli, a Jew, who argued Jews were inherently conservative because of their racial self-consciousness and “accumulated wealth.” During the 1848 revolutions, however, he decried “the once loyal Hebrew” among the ranks of “the Leveller,” seeking the destruction of Christianity and the abrogation of private property (see Domenico Losurdo’s excellent  Just as “cultural Marxism” is rooted in the anti-communist “Red Scare” rhetoric of the recent past, so too is the right-wing pundits’ appeals to free speech. During the Cold War, the conservative media regularly accused leftists of being pro-Soviet Union or not anti-Soviet Union enough. The ideological effect of this was to keep liberals on the defensive, to behave like reactionaries to show their anti-communist credentials. Under McCarthyism, liberals lined up to name names before the House Un-American Activities Committee to ruin the lives of friends and relatives just to illustrate their fidelity to the national religion. Today, conservative commentators demand liberals do the same or otherwise be guilty by association with the “loony left.” Best of all for conservatives, they do not even need expertise or even experience; hence, why they will line up behind the appropriateness of a 24-year-old woman to speak about something she knows absolutely nothing about. Instead, the only question that matters is directed at the reader, a challenge to stand up for “common sense” and “our side” in the Manichean conservative understanding of “good guys” and “bad guys,” us versus them, so that any issue (such as equal rights for transgender people) becomes one not of logic and fairness but emotion.

Just as “cultural Marxism” is rooted in the anti-communist “Red Scare” rhetoric of the recent past, so too is the right-wing pundits’ appeals to free speech. During the Cold War, the conservative media regularly accused leftists of being pro-Soviet Union or not anti-Soviet Union enough. The ideological effect of this was to keep liberals on the defensive, to behave like reactionaries to show their anti-communist credentials. Under McCarthyism, liberals lined up to name names before the House Un-American Activities Committee to ruin the lives of friends and relatives just to illustrate their fidelity to the national religion. Today, conservative commentators demand liberals do the same or otherwise be guilty by association with the “loony left.” Best of all for conservatives, they do not even need expertise or even experience; hence, why they will line up behind the appropriateness of a 24-year-old woman to speak about something she knows absolutely nothing about. Instead, the only question that matters is directed at the reader, a challenge to stand up for “common sense” and “our side” in the Manichean conservative understanding of “good guys” and “bad guys,” us versus them, so that any issue (such as equal rights for transgender people) becomes one not of logic and fairness but emotion. another refugee crisis, the Middle East and radical Islam remain constant features of headlines. An underappreciated fact about current events is the role of ideology, and how nationalism has given way to political Islam in much of the region. To understand the motivations of Islamists and the failure of liberals to triumph in the wake of the Arab Spring, it is valuable to look at regional history and understand how the decline of pan-Arabism and the poverty of liberalism has combined into the rise of Islamism and, in extreme cases, jihadism. Such examination shows that many of the present problems cannot be attributed to Islam or even political Islam as an ideology, but the ignorance of the West of its errors and its unwillingness to reign in local actors who are using sectarian and ethnic conflicts for their own benefit in a scramble to accumulate more influence.

another refugee crisis, the Middle East and radical Islam remain constant features of headlines. An underappreciated fact about current events is the role of ideology, and how nationalism has given way to political Islam in much of the region. To understand the motivations of Islamists and the failure of liberals to triumph in the wake of the Arab Spring, it is valuable to look at regional history and understand how the decline of pan-Arabism and the poverty of liberalism has combined into the rise of Islamism and, in extreme cases, jihadism. Such examination shows that many of the present problems cannot be attributed to Islam or even political Islam as an ideology, but the ignorance of the West of its errors and its unwillingness to reign in local actors who are using sectarian and ethnic conflicts for their own benefit in a scramble to accumulate more influence. successes in the foundation of the United Arab Republic and the Arab Federation (the 1958 unions of Syria and Egypt and Iraq and Jordan, respectively). Northern and southern Yemen did merge, although the current civil war being fought there imperils that legacy. Nevertheless, these events prove what an instrumental power pan-Arabism had in Middle Eastern state-building post-World War II, when many of these states finally obtained autonomy. You can also perceive its importance by the fact that the Baath Party, strongly oriented toward Arab nationalism, held power in Iraq before the 2003 invasion and still does in Syria.

successes in the foundation of the United Arab Republic and the Arab Federation (the 1958 unions of Syria and Egypt and Iraq and Jordan, respectively). Northern and southern Yemen did merge, although the current civil war being fought there imperils that legacy. Nevertheless, these events prove what an instrumental power pan-Arabism had in Middle Eastern state-building post-World War II, when many of these states finally obtained autonomy. You can also perceive its importance by the fact that the Baath Party, strongly oriented toward Arab nationalism, held power in Iraq before the 2003 invasion and still does in Syria.